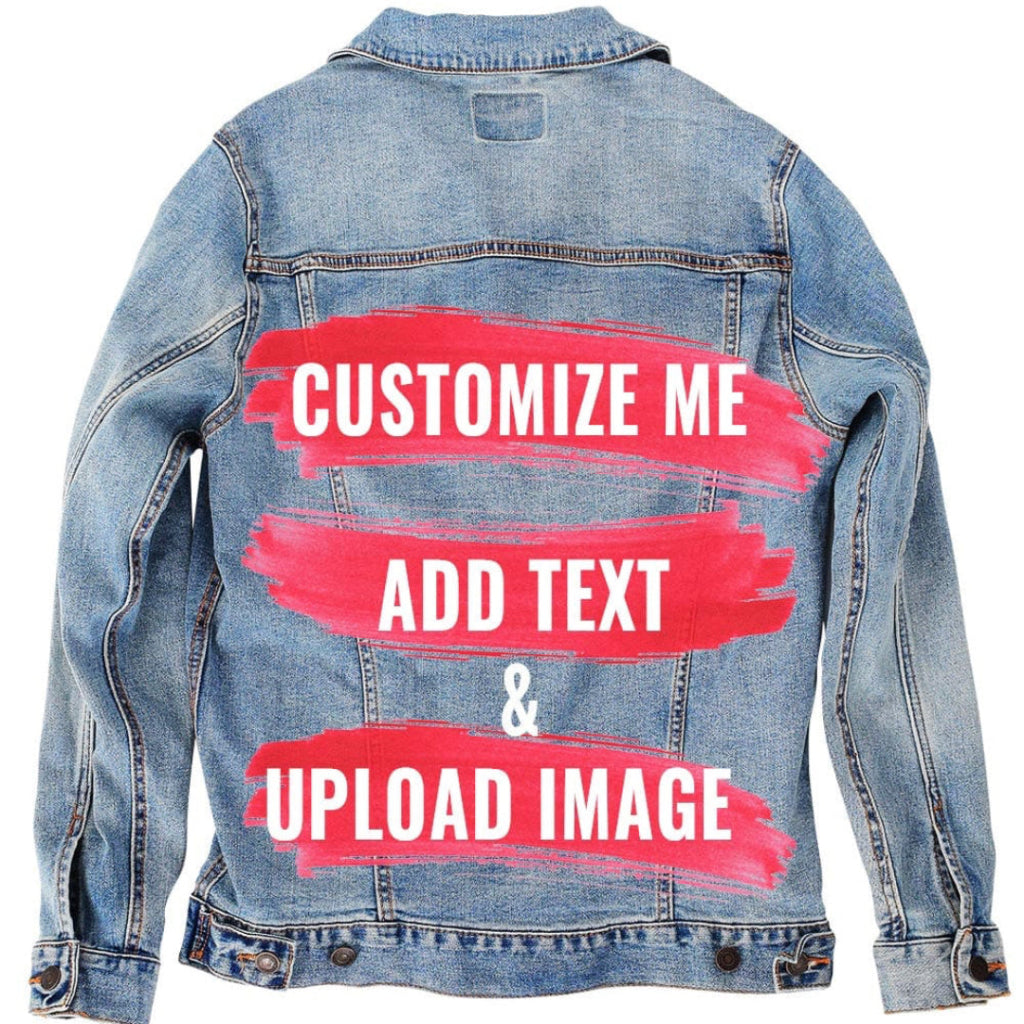

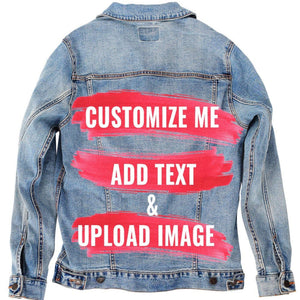

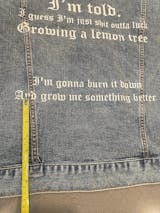

iIlustration of two horses set

before an ornate brown Celtic knot mandala in smoky bronze earth tones. the

circular knotwork weaves three stylized

horse figures from continuous over-and-under bands and triquetra-like sections.

in the foreground, a large dark brown horse with a flowing black mane dominates

one side, while a smaller black-and-white pinto horse trots through swirling

dust and spark-like splatter. this artwork is titled “Celtic Horse” and created

by artist Brigid Ashwood

You

drift first into the weight of the mane—black strands falling in thick,

wind-swept layers over the right side of the image, as if the air has just

moved through them. The large horse head emerges from shadowed brown, the face

turned slightly inward, a pale blaze cutting down the forehead like a quiet

strike of light. Below and forward, a smaller horse steps across the scene, one

front leg lifted mid-trot, black-and-white patches breaking across its body in

irregular shapes. Under its hooves, dust blooms outward in a warm, granular

burst, speckled with fine sparks and splatter that feel like earth caught

mid-motion.

Then

the eye is pulled back into the Celtic structure behind them, and here the

story becomes discipline. Intertwined within the knotwork are three horses,

and they are clearly horses—each with a defined head, neck, legs, and

tail—formed directly inside the triadic knot sections. One horse is placed in

the top section, shown in profile as if moving left, with a visible head

and neck and a flowing line suggesting mane along the crest. A second horse

occupies the lower-left section, angled differently, its body arcing

through a tighter cluster of knot crossings; the legs are drawn in simplified

lines but remain unmistakably equine. The third completes the triad in the lower-right

section, again in profile, the tail line trailing into the negative space

before the knot closes around it. These are not repeated stamps—they vary

subtly in pose and orientation, each one sitting within its own knot “window.”

You can see the micro-truth of the weave where a strand edge lightens as it

passes “over,” then deepens as it dips “under,” especially around the horses’

bodies where the knot must bend to contain them. On denim, those crossings

settle into the twill valleys and ride the ridges, making the horses feel

engraved—like the knotwork has been pressed into cloth. It matters because the

symbol holds motion without letting it scatter.

A

shift in mood happens when you compare the knot-horses to the painted pair in

front. The three intertwined horses behind are restrained—graphic, disciplined,

contained by structure. The foreground horses are alive with texture: the large

horse’s coat is rendered in smooth gradients of deep brown, with subtle

highlights catching the planes of the muzzle and cheek; the mane is built from

layered, directional strokes that separate into strands at the ends. The

smaller horse carries sharper contrast, patches of white and charcoal breaking

across the torso, the legs tapered and clean. On denim, those contrast

boundaries behave differently: white areas brighten and sharpen on white denim;

on black denim, they glow like moonlight against night; on stonewash, edges

soften into a lived-in realism. The emotional pulse lives in that

difference—myth behind, embodiment in front.

Color

becomes emotion in the bronze-brown palette. The knotwork reads like carved

wood or aged metal—dark bands with soft smoky fill behind them, giving the

circle depth without clutter. Small triquetra marks appear at points around the

design, punctuating the larger interlace like quiet seals. The dust burst below

turns the bottom of the image into motion—earth rising, scattering, then

settling—an echo of hooves you can almost hear.

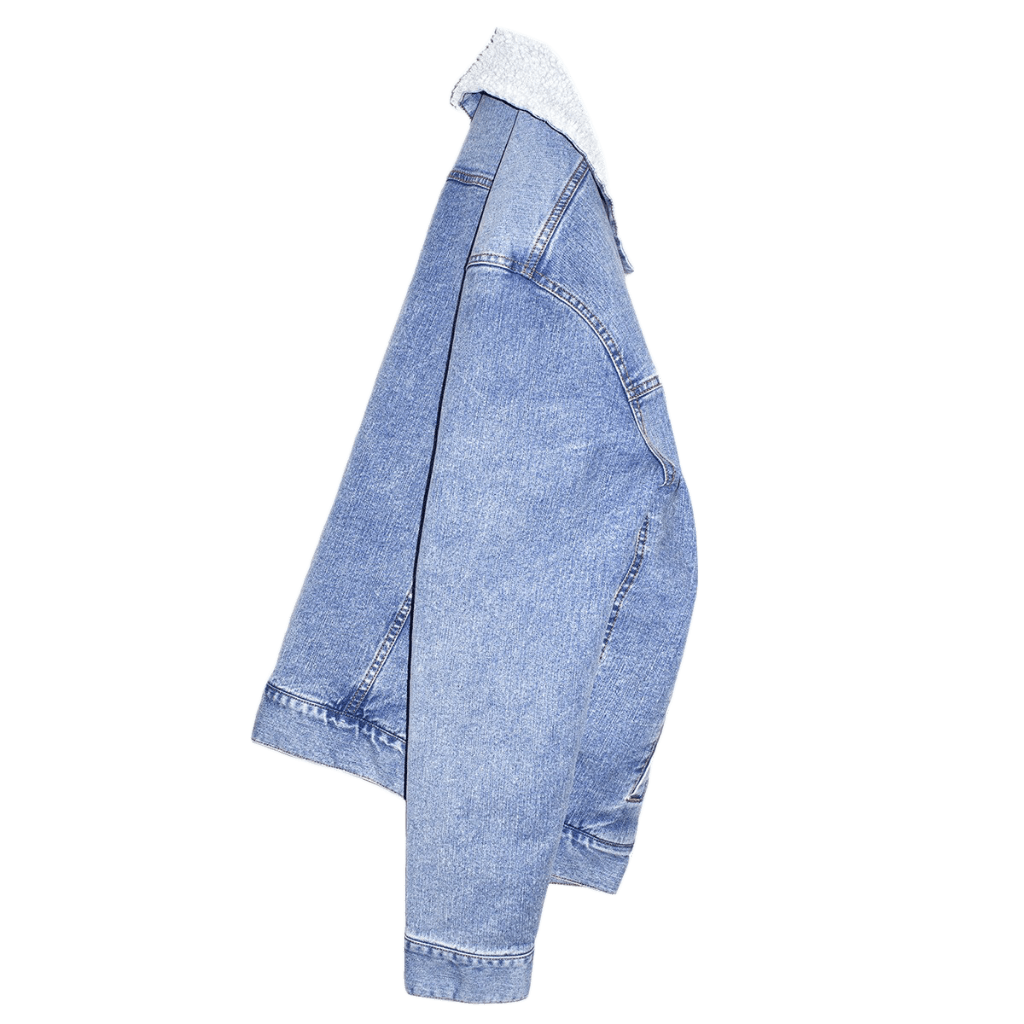

On

stonewashed denim, the knot becomes atmospheric first. The smoky bronze

field diffuses into the worn grain, and the over-under crossings soften

slightly while the three intertwined horses remain readable because

their silhouettes are clearly drawn within each section. The bronze tones warm

and spread, making the symbol feel older, more talismanic. The large horse head

in front gains a softer realism—highlights blur gently, and the mane’s strand

edges melt into velvety texture. The dust burst embeds into the fabric like

grit caught in cloth, so the motion feels remembered rather than frozen. As the

jacket moves, light breaks unevenly across the knot bands, and the horses

behind seem to shift depth subtly.

Stonewash

turns the piece into folklore—horse-power carried quietly, earth and breath

woven together.

On

white denim, everything becomes crisp and declarative. The knot’s

over-under logic reads cleanly, and the three intertwined horses are

easiest to count and trace—each one clearly contained in its own triadic

section. The bronze bands feel like inked engraving. The large horse’s blaze

stands out sharply, and the smaller horse’s black-and-white pattern becomes

graphic and striking. The dust burst brightens, individual specks and splatter

marks more visible. This clarity matters because it transforms the artwork into

statement—movement and lineage made unmistakable.

On

black denim, the scene deepens into something cinematic. The bronze knot

glows against the dark base like a burnished seal, and the three intertwined

horses feel carved into shadow—crossings deepening, loops reading like

channels. The large horse head partially merges into the black, but its

highlights and blaze emerge with intensity, and the mane becomes a dark

waterfall with faint sheen. The smaller horse’s white patches glow against the

darkness, and the dust burst becomes sparks—earth turned to firelight. As the

fabric folds, the knot crossings appear and disappear, and the three horses

inside seem to rotate slowly within the symbol.

On

black denim, the artwork feels like a vow of strength: three horses bound

into knotwork behind two living horses in the present, motion held, power

carried close.